- Home

- Andrzej Sapkowski

The Tower of Fools Page 7

The Tower of Fools Read online

Page 7

“It’s not so simple.” Reynevan blushed like a beetroot. “What will she gain if they catch and kill me? Or I, for that matter? But I shall find a way, never fear. Even if I have to disguise myself as Tristan did. Amor vincit omnia.”

Zawisza raised himself up in his saddle and broke wind. It was hard to tell if it was a comment or just the cabbage.

“One profit of this dispute,” he said, “is that we’ve begun to talk, for it is mournful to ride in silence with head hanging. Let’s talk on, my young Silesian. On any subject.”

Reynevan plucked up the courage to ask: “Why do you ride this way, sir? Isn’t it quicker to get to Moravia from Krakow via Racibórz? And Opava?”

“Perhaps it is,” agreed Zawisza. “But I, you see, cannot bear the Lords of Racibórz. The recently deceased Duke Jan, may the Lord keep him in His care, was a whoreson who sent assassins to dispatch my comrade Přemysl. Jan’s young lad, Mikołajek, follows boldly in his father’s footsteps, so they say. Furthermore, I chose a roundabout route because I had things to discuss with Kantner in Oleśnica and am to report what Jogaila had said about him. On top of that, the route through Lower Silesia usually abounds with… attractions. Although I see that opinion is something of an exaggeration.”

“Ah!” Reynevan guessed astutely. “That is why you ride in full armour, and on a war horse! You are looking for a fight. Am I right?”

“You are,” Zawisza the Black calmly agreed. “They said that Silesia teems with Raubritter robber knights.”

“Not here. It’s safe here. That’s why it’s so thronged.”

Indeed, they couldn’t complain of a lack of company, for the road was busy with traffic heading in the opposite direction, from Brzeg to Oleśnica. They’d already passed several merchants on heavily laden wagons cutting deep ruts, escorted by a dozen or more armed men with thuggish faces, and a column of pitch makers weighed down by full goatskins, their presence announced in advance of their arrival by the sharp smell of their wares. A knight rode by with a lady and a small retinue. His Bavarian armour was opulent, and the fork-tailed lion rampant on his shield declared his membership of the Unruh family. Recognising Zawisza’s coat of arms at once, the knight greeted him with a proud bow which clearly indicated that the Unruh didn’t consider themselves the Zawiszas’ inferiors. The knight’s companion, wearing a pale mauve dress, was riding side-saddle on a gorgeous dark bay mare. Surprisingly, she wore no headdress, and the wind was freely playing in her golden hair. As she rode alongside, the woman raised her head, smiled delicately and granted Reynevan, who was staring at her, such an intense come-hither look that the young man trembled.

“Oh my,” said Zawisza soon after. “You won’t die of natural causes, my lad.”

And farted. With the force of a medium-calibre bombard.

“In order to prove,” said Reynevan, “that I don’t begrudge you your spitefulness or taunts, I’ll cure you of your flatulence.”

“How, pray tell?”

“You will see. What we need is a shepherd.”

A shepherd appeared quite soon, but on seeing some horsemen turning from the highway towards him took panicked flight, plunged into the thicket and vanished like the morning mist. Only his bleating sheep remained.

“We should have laid a trap for him,” observed Zawisza, standing up in his stirrups. “We won’t catch up with him over that bumpy ground. Judging by the speed he set off at, he’s probably crossed the Odra by now.”

“And the Nysa, too,” added Wojciech, the knight’s esquire, demonstrating both a ready wit and a knowledge of geography.

Reynevan was unmoved by the teasing. He dismounted and walked purposefully over to the shepherd’s hut, from which he emerged a moment later holding a large bunch of herbs.

“I didn’t need a shepherd,” he calmly explained. “Just these. And a dash of boiling water. Any chance of a cooking pot?”

“Whatever you need,” said Wojciech dryly.

“If you have to boil water, we’ll make a stop.” Zawisza looked up at the sky. “And a lengthy one, for night approaches.”

Zawisza the Black leaned comfortably against his sheepskin-covered saddle, looked into the mug he had just drained and sniffed.

“In truth, it tastes like sun-warmed moat water and stinks of tomcat,” he announced, “but it works. My gratitude, Reinmar. It is a falsehood, I see, that universities teach a young man naught but drunkenness, lewdness and vulgar speech.”

“A whit of knowledge about herbs, nothing more,” replied Reynevan modestly. “What really helped you, Lord Zawisza, was casting off your armour and resting in a more comfortable position—”

“You are too modest,” interrupted the knight. “I know my own limits, know how long I’m capable of enduring in the saddle and wearing armour. Indeed, I often journey at night with a lantern rather than resting—it shortens the journey, and there’s always the chance that somebody might accost me in the dark, which provides a welcome diversion. But since you claim this is a peaceful spot, why weary the horses? Let us sit by the fire until dawn and tell tales… That is also amusement, after all. Perhaps not as good as disembowelling a few Raubritters, but still.”

The fire crackled merrily, lighting up the night. An appetising aroma drifted up from the grease dripping from sausages and chunks of bacon sizzling on sticks grilled by Esquire Wojciech and the servants. Zawisza’s retinue kept their silence and a suitable distance, but Reynevan could still see the gratitude in the glances they were casting him. They clearly didn’t share their master’s fondness for riding through the dark hours by lantern light.

The sky above the trees twinkled with stars. The night was cool.

“Yeees…” Zawisza rubbed his belly with both hands. “Your potion has eased me, truly—what was that magical herb, some kind of mandrake? And why did you seek it in a shepherd’s hut?”

“After Saint John’s Day,” explained Reynevan, glad to be able to show off, “shepherds gather various herbs known only to them and dry them in their huts. And they make from them a decoction, which—”

“Which is given to their flock,” Zawisza calmly interrupted. “You mean you treated me like a bloated ewe. Well, if it helped—”

“Don’t mock me, Sir Zawisza. Folk wisdom is prodigious, and none of the great physicians or alchemists scorned it. Medicine has benefitted greatly from the common folk, shepherds in particular, for they have vast knowledge about herbs and their medicinal—and other—powers.”

“Indeed?”

“Indeed.” Reynevan nodded, moving closer to the fire to be more visible. “You’d not believe, Sir Zawisza, how much power is hidden in this bundle, in this bunch of dry herbs from a shepherd’s shack, which isn’t worth a brass farthing. Infusions made from them work miracles, yet few physicians know how effective they are. One must also invoke the patron saints of shepherds when giving these herbs to one’s flock.”

“What you were mumbling over the cooking pot wasn’t about saints.”

“It wasn’t,” Reynevan confessed, clearing his throat. “I told you, folk wisdom—”

“That wisdom reeked of the stake,” Zawisza said, his tone serious. “In your shoes, I’d be careful who I treated and with whom I spoke. I’d be careful, Reinmar.”

“I will.”

“While I,” Esquire Wojciech spoke up, “think that if witchcraft exists, it’s better to be versed in it than not. I think—”

He fell silent, seeing Zawisza’s menacing look.

“And I think,” the knight said sharply, “that all the evil of this world comes from thinking. Particularly among people who have no inclination at all towards it.”

Wojciech leaned even lower over the harness he was cleaning and greasing. Reynevan waited a little longer before speaking again.

“Sir Zawisza?”

“Aye?”

“In the tavern, during the dispute with that Dominican, you didn’t conceal… How should I put it…? That you support the Czech Hussites. Or

that you’re more for them than against, at least.”

“And what, you immediately label such thoughts as heresy?”

“Among others,” Reynevan admitted a moment later. “But I’m more intrigued by—”

“By what?”

“By what happened at the Battle of Německý Brod in twenty-two, when you were taken captive. For legends are already circulating—”

“Such as?”

“That the Hussites captured you because you felt it beneath you to flee but couldn’t fight, being an emissary.”

“Is that the rumour?”

“It is. But also that… That King Sigismund shamefully fled and left you in the lurch.”

Zawisza said nothing for a time.

“And you would like to know the truth?” he finally said.

“If,” Reynevan replied hesitantly, “it would not inconvenience you—”

“Why would it inconvenience me? Conversation passes the time agreeably. Why not then converse?”

Despite his declaration, the knight from Garbów again fell silent for a long time and played with the empty mug. Reynevan wasn’t sure if Zawisza was waiting for a question, but he didn’t hurry to ask one. Rightly, as it turned out.

“Methinks I ought to begin at the beginning,” said Zawisza, “when Jogaila—sorry, I should say the Polish King Władysław II—sent me to the King of Hungary on a sensitive mission pertaining to his marriage to Queen Euphemia-Sophia, King Sigismund’s sister-in-law and widow of the late Czech King Wenceslaus. Nothing came of it, of course, for in the end King Władysław preferred Sophia of Halshany, but that wasn’t known then. King Władysław ordered me to make the necessary arrangements with Sigismund, mainly with regard to the dowry. So off I went. Not to Pressburg or Buda, though, but to Moravia, from where Sigismund was just setting out on another crusade to deal with his disobedient subjects, with the firm intention of capturing Prague and rooting out Hussite heresy in Bohemia once and for all.

“When I arrived on Saint Martin’s Day, Sigismund’s crusade was advancing quite satisfactorily, although his army was somewhat weakened. Most of the Lusatian forces commanded by Komtur Rumpold had returned home, content with having ravaged the lands around Chrudim. The Silesian contingent, which included our recent host Duke Konrad Kantner, had also returned home. Consequently, King Sigismund’s march to Prague was only supported by Albrecht’s Austrian knights and the Moravian army of the Bishop of Olomouc. Even so, Sigismund’s Hungarian cavalry alone numbered more than ten thousand…”

Zawisza fell silent for a time, staring into the crackling fire.

“Like it or not,” he continued, “I had to take part in the crusade in order to negotiate Jogaila’s marriage with Sigismund, and consequently witnessed all sorts of terrible things, including the capture of Polička and the slaughter that followed it.”

The servants and the esquire sat motionless. Maybe they were sleeping—Zawisza’s voice was soft and monotonous, perhaps soporific for people who knew the story already or had experienced these events themselves.

“After Polička, Sigismund set off for Kutná Hora. General Žižka barred his way and repelled several charges by the Hungarian cavalry, but when word of the city being taken by treachery got out, he retreated. The king’s men entered Kutná Hora, intoxicated by their triumph—they had defeated Žižka. Žižka himself had fled from them! And then Sigismund committed an unforgivable error, although I and Filippo degli Scolari tried to dissuade him—”

“You mean Pippo Spano? The celebrated Florentine condottiere?”

“Yes, but don’t interrupt, lad. Against the advice of myself and Pippo, King Sigismund, convinced that the Czechs had fled in panic and wouldn’t stop till they reached Prague, let the Hungarians scour the area for winter quarters, because the frost was bitter. So, the Magyars dispersed and spent Christmastide pillaging, assaulting womenfolk, burning down villages and murdering anyone they considered heretics or their supporters. Which meant anybody they came across.

“Fire lit up the night sky, smoke filled it during the day, and in Kutná Hora, King Sigismund feasted and held trials. And then, on the morning of the Epiphany, the news arrived that Žižka was approaching. Žižka hadn’t fled but merely fallen back, regrouped and gained reinforcements, and was now heading for Kutná Hora with the full force of the Tábor and Prague behind him. ‘He’s in Kaňk, he’s in Nebovidy!’ And what did the valiant crusaders do on hearing that? Seeing there was too little time to gather the men dispersed around the countryside, they ran away, leaving plenty of arms and goods and burning down the town behind them. For a while, Pippo Spano brought the panic under control and halted the forces halfway between Kutná Hora and Německý Brod.

“And then, from a distance… Laddie, I’d never seen or heard anything like that before, and I’ve seen and heard plenty. The Taborites and Praguians marched on us, bearing standards and monstrances, in a splendid, disciplined array, their songs booming like thunder. On rolled their infamous battle wagons, from which handgonnes, cannons and trestle guns leered at us…

“And what did those brave crusaders do then? Before the Hussites were even within range, Sigismund’s entire army fled headlong in utter panic to Německý Brod. To a man, they ran screaming from a crowd of peasants in bast shoes whom they had jeered at not long before, casting down weapons they had mainly raised against unarmed men during this entire infernal crusade. They fled before my astonished eyes, laddie, as though they were scared of… the truth. Of the slogan VERITAS VINCIT embroidered onto the Hussite standards.

“Most of the Hungarians and armoured lords managed to flee to the left bank of the frozen Sázava. Then the ice broke. I advise you, lad, with all my heart, if you have to fight in winter, never flee across ice wearing armour. Never.”

Reynevan vowed to himself that he never would.

Zawisza puffed and cleared his throat. “As I was saying,” he went on, “the knights, though they had lost their honour, saved their skins. Mostly. But the foot soldiers were caught by the Hussites and bludgeoned, and the snow on the road was stained red for two miles, from the village of Habry to the outskirts of Německý Brod.”

“And you, sir? What—?”

“I didn’t flee with the king’s knights, nor when Pippo Spano and Jan of Hardegg fled—and I must salute them, for they were some of the last to flee and put up a fight as they did so. Contrary to the tales you’ve heard, I also fought, and fought hard, emissary or not. And I didn’t fight alone, for there were a few Poles and Moravian lordlings at my side, men who didn’t like running away any more than I did. All I’ll say of that battle is that we fought, and many are the Czech mothers who weep because of me. But nec Hercules—”

The servants, it turned out, were not asleep. For one suddenly jumped to his feet, as though stung by a viper, a second cried in a stifled voice, and a third drew a short sword with a grating sound as Esquire Wojciech seized a crossbow. Zawisza’s harsh voice and imperious gesture quietened them all.

Something emerged from the gloom.

At first, they thought it was a fragment, a swirl of darkness limned by anthracite blackness in the flickering murk of the night, lit up by flashes of fire. When the flame burned more fiercely, that cloud of darkness, although losing none of its blackness, assumed a shape, and a form. A stocky, plump form, but not that of a bird ruffling up its feathers, nor a beast bristling its fur. The creature’s head, pulled into its shoulders, was topped by a pair of large, pointed feline ears, sticking up straight and unmoving.

Without taking his eyes off the creature, Wojciech slowly put the crossbow down. One of the servants appealed for the intercession of Saint Kinga, but he was also quietened by a gesture from Zawisza. Not violent, but charged with power and authority.

“Greetings, stranger,” said the knight from Garbów, astonishingly calm. “Fear not and take your seat by our campfire.”

The creature moved its head and Reynevan saw a fleeting flash of large eyes reflecting red

flame.

“Fear not and take a seat,” repeated Zawisza in a voice that was kindly and hard at the same time. “You need not fear us.”

“I fear you not,” said the creature hoarsely, to everyone’s utter astonishment. Then the creature held out a paw. Reynevan would have sprung back had he not been too afraid to move. He suddenly realised in astonishment that the paw was pointing at the arms on Zawisza’s shield. Then, to his even greater astonishment, the creature pointed at the cauldron with the herbal infusion.

“Sulima and a herbalist,” the creature croaked. “Rectitude and knowledge. What is there to fear? I fear not. My name is Hans Mein Igel.”

“Greetings to you, Hans Mein Igel. Be you hungry? Or thirsty?”

“No. It came to sit down. And listen. For it heard their words. And came to listen.”

“Please, be our guest.”

The creature approached the campfire, bristled up into a ball and stopped moving.

“Aaaye.” Zawisza’s composure was truly astonishing. “Where was I?”

“You were…” Reynevan swallowed, regaining his speech. “You were saying nec Hercules.”

“That is so,” croaked Hans Mein Igel.

“Aye,” said the knight freely, “that I was. Nec Hercules, the Hussites overcame us. Indeed, we were fortunate to be attacked by the cavalry, for the Tábor flailmen do not know the words ‘mercy’ or ‘ransom.’ When they finally hauled me from the saddle, one of the knights remaining with me managed to shout out who I was, that I had fought at Grunwald with Žižka and Jan Sokol of Lamberk.”

Reynevan gasped softly on hearing the distinguished names. Zawisza was silent for a long time.

“You probably know the rest,” he said finally, “for the rest cannot differ much from the legend.”

Reynevan and Hans Mein Igel nodded in silence. It was a good while before the knight took up the story again.

something ends something begins sapkowski

something ends something begins sapkowski The Last Wish

The Last Wish Baptism of Fire

Baptism of Fire Blood of Elves

Blood of Elves Lastavičja Kula

Lastavičja Kula Gospodarica Jezera

Gospodarica Jezera Vatreno Krštenje

Vatreno Krštenje Sezona Oluja

Sezona Oluja Lady of the Lake

Lady of the Lake The Road With No Return

The Road With No Return Time of Contempt

Time of Contempt Mač Sudbine

Mač Sudbine The Malady and Other Stories: An Andrzej Sapkowski Sampler

The Malady and Other Stories: An Andrzej Sapkowski Sampler The Saga of the Witcher

The Saga of the Witcher The Tower of Fools

The Tower of Fools Vreme Prezira

Vreme Prezira Introducing the Witcher

Introducing the Witcher Stephen Hulin

Stephen Hulin The Time of Contempt

The Time of Contempt The Sword of Destiny

The Sword of Destiny Season of Storms

Season of Storms The Tower of Swallows

The Tower of Swallows The Last Wish: Introducing The Witcher

The Last Wish: Introducing The Witcher The Lady of the Lake

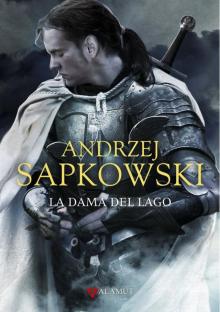

The Lady of the Lake