- Home

- Andrzej Sapkowski

The Tower of Fools Page 3

The Tower of Fools Read online

Page 3

Nicolaus wasn’t as lucky. His horse skidded to a halt in front of the frame and collided with it, slipping on the mud and scraps of meat and fat. The youngest Stercza shot over his horse’s head, with very unfortunate results. He flew belly-first right onto a scythe used for scraping leather which the tanners had left propped up against the frame.

At first, Nicolaus had no idea what had happened. He got up from the ground, caught hold of his horse, and only when it snorted and stepped back did his knees sag and buckle beneath him. Still not really knowing what was happening, the youngest Stercza slid across the mud after the panicked horse, which was still moving back and snorting. Finally, as he released the reins and tried to get to his feet again, he realised something was wrong and looked down at his midriff.

And screamed.

He dropped to his knees in the middle of a rapidly spreading pool of blood.

Dieter Haxt rode up, reined in his horse and dismounted. A moment later, Wolfher and Wittich followed suit.

Nicolaus sat down heavily. Looked at his belly again. Screamed and then burst into tears. His eyes began to glaze over as the blood gushing from him mingled with the blood of the oxen and hogs butchered that morning.

“Nicolaaaaus!” yelled Wolfher.

Nicolaus of Stercza coughed and choked. And died.

“You are dead, Reinmar of Bielawa!” Wolfher of Stercza, pale with fury, bellowed towards the gate. “I’ll catch you, kill you, destroy you. Exterminate you and your entire viperous family. Your entire viperous family, do you hear?”

Reynevan didn’t. Amid the thud of horseshoes on the bridge planks, he was leaving Oleśnica and dashing south, straight for the Wrocław highway.

Chapter Two

In which the reader finds out more about Reynevan from conversations involving various people, some kindly disposed and others quite the opposite. Meanwhile, Reynevan himself is wandering around the woods near Oleśnica. The author is sparing in his descriptions of that trek, hence the reader—nolens volens—will have to imagine it.

“Sit you down, gentlemen,” said Bartłomiej Sachs, the burgermeister of Oleśnica, to the councillors. “What’s your pleasure? Truth be told, I have no wines to regale you with. But ale, ho-ho, today I was brought some excellent matured ale, first brew, from a deep, cold cellar in Świdnica.”

“Beer it is, then, Master Bartłomiej,” said Jan Hofrichter, one of the town’s wealthiest merchants, rubbing his hands together. “Ale is our tipple, let the nobility and diverse lordlings pickle their guts in wine… With my apologies, Reverend…”

“Not at all,” replied Father Jakub of Gall, parish priest at the Church of Saint John the Evangelist. “I’m no longer a nobleman, I’m a parson. And a parson, naturally, is ever with his flock, thus it doesn’t behove me to disdain beer. And I may drink, for Vespers have been said.”

They sat down at the table in the huge, low-ceilinged, whitewashed chamber of the town hall, the usual location for meetings of the town council. The burgermeister was in his customary seat, back to the fireplace, with Father Gall beside him, facing the window. Opposite sat Hofrichter, beside him Łukasz Friedmann, a sought-after and wealthy goldsmith, in his fashionably padded doublet, a velvet beret resting on curled hair, every inch the nobleman.

The burgermeister cleared his throat and began, without waiting for the servant to bring the beer. “And what is this?” he said, linking his hands on his prominent belly. “What have the noble knights treated us to in our town? A brawl at the Augustinian priory. A chase on horseback through the streets. A disturbance in the town square, several folk injured, including one child gravely. Belongings destroyed, goods marred—such significant material losses that mercatores et institores were pestering me for hours with demands for compensation. In sooth, I ought to pack them off with their plaints to the Lords Stercza!”

“Better not,” Jan Hofrichter advised dryly. “Though I also hold that our noblemen have been lately passing unruly, one can neither forget the causes of the affair nor of its consequences. For the consequence—the tragic consequence—is the death of young Nicolaus of Stercza. And the cause: licentiousness and debauchery. The Sterczas were defending their brother’s honour, pursuing the adulterer who seduced their sister-in-law and besmirched the marital bed. In truth, in their zeal they overplayed a touch—”

The merchant stopped speaking under Father Jakub’s telling gaze. For when Father Jakub signalled with a look his desire to express himself, even the burgermeister himself fell silent. Jakub Gall was not only the parish priest of the town’s church, but also secretary to Konrad, Duke of Oleśnica, and canon in the Chapter of Wrocław Cathedral.

“Adultery is a sin,” intoned the priest, straightening his skinny frame behind the table. “Adultery is also a crime. But God punishes sins and the law punishes crimes. Nothing justifies mob law and killings.”

“Yes, yes,” agreed the burgermeister, but fell silent at once and devoted all his attention to the beer that had just arrived.

“Nicolaus of Stercza died tragically, which pains us greatly,” added Father Gall, “but as the result of an accident. However, had Wolfher and company caught Reinmar of Bielawa, we would be dealing with a murder in our jurisdiction. We know not if there might yet be one. Let me remind you that Prior Steinkeller, the pious old man severely beaten by the Sterczas, is lying as if lifeless in the Augustinian priory. If he expires as a result of the beating, there’ll be a problem. For the Sterczas, to be precise.”

“Whereas, regarding the crime of adultery,” said the goldsmith Łukasz Friedmann, examining the rings on his manicured fingers, “mark, honourable gentlemen, that it is not our jurisdiction at all. Although the debauchery occurred in Oleśnica, the culprits do not come under our authority. Gelfrad of Stercza, the cuckolded husband, is a vassal of the Duke of Ziębice. As is the seducer, the young physician, Reinmar of Bielawa—”

“The debauchery took place here, as did the crime,” said Hofrichter firmly. “And it was a serious one, if we are to believe what Stercza’s wife disclosed at the Augustinian priory—that the physician beguiled her with spells and used sorcery to entice her to sin. He compelled her against her will.”

“That’s what they all say,” the burgermeister boomed from the depths of his mug.

“Particularly when someone of Wolfher of Stercza’s ilk holds a knife to their throat,” the goldsmith added without emotion. “The Reverend Father Jakub was right to say that adultery is a felony—a crimen—and as such demands an investigation and a trial. We do not wish for familial vendettas or street brawls. We shall not allow enraged lordlings to raise a hand against men of the cloth, wield knives or trample people in city squares. In Świdnica, a Pannewitz went to the tower for striking an armourer and threatening him with a dagger. Which is proper. The times of knightly licence must not return. The case must go before the duke.”

“All the more so since Reinmar of Bielawa is a nobleman and Adèle of Stercza a noblewoman,” the burgermeister confirmed with a nod. “We cannot flog him, nor banish her from the town like a common harlot. The case must come before the duke.”

“Let’s not be too hasty with this,” said Father Gall, gazing at the ceiling. “Duke Konrad is preparing to travel to Wrocław and has a multitude of matters to deal with before his departure. The rumours have probably already reached him—as rumours do—but now isn’t the time to make them official. Suffice it to postpone the matter until his return. Much may be resolved by then.”

“I concur.” Bartłomiej Sachs nodded again.

“As do I,” added the goldsmith.

Jan Hofrichter straightened his marten-fur calpac and blew the froth from his mug. “For the present, we ought not to inform the duke,” he pronounced. “We shall wait until he returns, I agree with you on that, honourable gentlemen. But we must inform the Holy Office, and fast, about what we found in the physician’s workshop. Don’t shake your head, Master Bartłomiej, or make faces, honourable Master Łukasz. And you, Rev

erend, stop sighing and counting flies on the ceiling. I desire this about as much as you do, and the same goes for the Inquisition. But many were present at the opening of the workshop. And where there are many people, at least one of them is reporting back to the Inquisition. And when the Inquisitor arrives in Oleśnica, we’ll be the first to be asked why we delayed.”

“So I will explain the delay,” said Father Gall, tearing his attention away from the ceiling. “I, in person, because it’s my parish and the responsibility to inform the bishop and the papal Inquisitor falls on me. It is also for me to judge whether the circumstances justify the summoning and bothering of the Curia and the Office.”

“Isn’t the witchcraft that Adèle of Stercza was screaming about at the Augustinian priory a circumstance?” persisted Jan Hofrichter. “Isn’t the workshop itself? Aren’t the alchemic alembic and pentagram on the floor? The mandrake? The skulls and skeletons’ hands? The crystals and looking glasses? The bottles and flacons containing the Devil only knows what filth and venom? The frogs and lizards in specimen jars? Aren’t they circumstances?”

“They are not,” said Father Gall. “The Inquisitors are serious men. What interests them is inquisitio de articulis fidei, not old wives’ tales, superstitions and frogs. I have no intention of bothering them with that.”

“And the books?” said Hofrichter. “The ones we have here?”

“The books ought first to be examined,” replied Jakub Gall calmly. “Thoroughly and unhurriedly. The Holy Office doesn’t forbid reading. Nor the owning of books.”

“Two people have just gone to the stake in Wrocław,” Hofrichter said gloomily, “for owning a book, or so the rumour runs.”

“Not for owning books,” the parish priest countered dryly, “but for contempt of court, for an impertinent refusal to renounce the content propagated in those books, among which were the writings of Wycliffe and Huss, the Lollard Floretus, the Articles of Prague and numerous other Hussite pamphlets and tracts. I don’t see anything like that here, among the books confiscated from Reinmar of Bielawa’s workshop. I see almost exclusively medical tomes. Which, as a matter of fact, are mainly or even entirely the property of the Augustinian priory’s scriptorium.”

“I repeat,” Jan Hofrichter stood up and went over to the books spread out on the table, “I repeat, I am not at all keen to involve either the bishop or the papal Inquisition—I don’t wish to denounce anyone or see anyone sizzling at the stake. But this concerns our arses and ensuring that we aren’t accused of possessing these books, either. And what do we have here? Apart from Galen, Pliny and Strabo? Albertus Magnus, De vegetabilis et plantis… Magnus, ha, a nickname right worthy of a wizard. And here, well, well, Shapur ibn Sahl… Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi… Pagans! Saracens!”

“The works of these Saracens are taught at Christian universities,” Łukasz Friedmann calmly explained, examining his rings, “as medical authorities. And your ‘wizard’ is Albert the Great, the Bishop of Regensburg, a learned theologian.”

“You don’t say? Hmmm… Let’s keep looking… See! Causae et curae, written by Hildegard of Bingen. Undoubtedly a witch, that Hildegard!”

“Not really,” Father Gall said, smiling. “Hildegard of Bingen, a visionary, called the Sibyl of the Rhine. She died in an aura of saintliness.”

“If you say so… But what’s this? John Gerard, A Generall… Historie… of Plantes… I wonder what tongue this is. Hebrew, perhaps. But he’s probably another saint. And here we have Herbarius, by Thomas of Bohemia—”

“What did you say?” Father Jakub lifted his head. “Thomas of Bohemia?”

“That’s what is written here.”

“Show me. Hmmm… Interesting, interesting… Everything, it turns out, remains in the family. And revolves around the family.”

“What family?”

“So close to home, it couldn’t be closer.” Łukasz Friedmann still appeared to be utterly absorbed by his rings. “Thomas of Bohemia is the great-grandfather of our Reinmar, the lover of other men’s wives, the man who has caused us such confusion and trouble.”

“Thomas of Bohemia…” The burgermeister frowned. “Also called Thomas the Physician. I’ve heard of him. He was a companion of one of the dukes… I can’t recall which…”

“Duke Henry VI of Wrocław,” Friedmann the goldsmith calmly offered in explanation.

“It is also said,” Hofrichter interrupted, nodding in confirmation, “that he was a wizard and a heretic.”

“You’re worrying that sorcery like a bone, Master Jan,” the burgermeister said with a grimace. “Let it go.”

“Thomas of Bohemia was a man of the cloth,” the priest informed them in a slightly harsh voice, “a canon in Wrocław and later a diocesan suffragan bishop and the titular Bishop of Zarephath. He knew Pope Benedict XII personally.”

“All sorts of things were said about that pope,” added Hofrichter, not letting up. “And witchcraft occurred among protonotaries apostolic, too. When in office, Inquisitor Schwenckefeld—”

“Just drop it, would you,” Father Jakub said, cutting him off. “We have other concerns here.”

“Indeed,” confirmed the goldsmith. “And I know what they are. Duke Henry had no male issue, but three daughters. Our Father Thomas of Bohemia took the liberty of a dalliance with the youngest, Margaret.”

“The duke permitted it?” Hofrichter asked. “Were they such good friends?”

“The duke was dead by then,” the goldsmith explained, “so Duchess Anne either didn’t see it or chose not to. Although not yet a bishop, Thomas of Bohemia was on excellent terms with the other nobles of Silesia. For imagine, gentlemen, somebody who not only visits the Holy Father in Avignon, but is also capable of removing kidney stones so skilfully that after the operation, the patient doesn’t just still have a prick—he can even get it up. It is widely believed that it is thanks to Thomas that we still have Piasts in Silesia today. He aided both men and women with equal skill. And couples, too, if you understand my meaning.”

“I fear I do not,” said the burgermeister.

“He was able to help married couples who were unsuccessful in the bedchamber. Now do you understand?”

“Now I do.” Jan Hofrichter nodded. “So, he probably bedded the Wrocław princess according to medical principles, too. Of course, there was issue from that.”

“Naturally,” replied Father Jakub, “and the matter was dealt with in the usual way. Margaret was sent to the Poor Clares convent and the child, Tymo, ended up with Duke Konrad in Oleśnica, who raised him as his own. Thomas of Bohemia grew in importance everywhere, in Silesia and at the court of Charles IV in Prague, so the boy had a career guaranteed from childhood onwards—an ecclesiastical career, naturally, all dependent on what kind of intelligence he displayed. Were he dim, he’d become a village priest. Were he reasonably bright, he’d be made an abbot in a Cistercian monastery somewhere. Were he intelligent, a chapter of one of the collegiates would be waiting for him.”

“How did he turn out?” Hofrichter asked.

“Quite bright. Handsome, like his father. And valiant. As a young man, the future priest fought against the Greater Poles beside the younger duke, the future Konrad the Elder. He fought so bravely that nothing was left but to dub him a knight and grant him a fiefdom. And thus, the young priest Tymo was dead, and long live Sir Tymo Behem of Bielawa. Sir Tymo, who soon became even better connected by wedding the youngest daughter of Heidenreich Nostitz, from which union Henryk and Tomasz were born. Henryk took holy orders, was educated in Prague and until his quite recent death was the scholaster at the Church of the Holy Cross in Wrocław. Tomasz, meanwhile, wedded Boguszka, the daughter of Miksza of Prochowice, who bore him two children, Piotr and Reinmar, this Reynevan who is causing us so much trouble.”

Jan Hofrichter nodded and sipped beer from his mug. “And this Reinmar-Reynevan who’s in the habit of seducing other men’s wives… what is his position at the Augustinian priory? An oblatus? A

conversus? A novice?”

“Reinmar of Bielawa,” Father Jakub said, smiling, “is a physician, schooled at Charles University in Prague. Before that, the boy attended the cathedral school in Wrocław, then learned the arcana of herbalism from the apothecaries of Świdnica and the monks of the monastery of the Hospital of the Holy Ghost in Brzeg. It was those monks and his uncle Henryk, the Wrocław scholaster, who placed him with the Augustinians, who are skilled in herbalism. The boy worked honestly and eagerly in the hospital and the leper house, proving his vocation. Later on, he studied medicine in Prague, again benefitting from his uncle’s patronage and the money his uncle received from the canonry. He clearly applied himself to his studies, for after two short years he was a Bachelor of Arts. He left Prague right after the… erm—”

“Right after the Defenestration,” the burgermeister said, undaunted. “Which clearly shows he had nothing in common with Hussite heresy.”

“Nothing links him with it,” Friedmann the goldsmith calmly confirmed. “Which I know from my son, who also studied in Prague at the same time.”

“It was also very fortunate,” added Burgermeister Sachs, “that Reynevan returned to Silesia, and to us, in Oleśnica, and not to the Ziębice duchy, where his brother Piotr serves Duke Jan as a knight. Reynevan is a good and bright lad, though young, and so able at herbalism that you’d be hard-pressed to find his equal. He treated the carbuncles that appeared on my wife’s… body, and cured my daughter’s chronic cough. He gave me a decoction for my suppurating eyes, which cleared up as if by magic…” The burgermeister fell silent, cleared his throat and shoved his hands into the fur-trimmed sleeves of his coat.

Jan Hofrichter looked at him keenly. “Now all is clear to me about this Reynevan,” he finally pronounced, “I know everything. Misbegotten, albeit, but of Piast blood. A bishop’s son. A favourite of dukes. Kin of the Nostitz family. The nephew of the scholaster at Wrocław Collegiate Church. A friend of rich men’s sons at university. On top of that, as if that weren’t enough, a conscientious physician, almost a miracle worker, capable of winning the gratitude of the powerful. And of what did he cure you, Reverend Father Jakub? From what complaint, out of interest?”

something ends something begins sapkowski

something ends something begins sapkowski The Last Wish

The Last Wish Baptism of Fire

Baptism of Fire Blood of Elves

Blood of Elves Lastavičja Kula

Lastavičja Kula Gospodarica Jezera

Gospodarica Jezera Vatreno Krštenje

Vatreno Krštenje Sezona Oluja

Sezona Oluja Lady of the Lake

Lady of the Lake The Road With No Return

The Road With No Return Time of Contempt

Time of Contempt Mač Sudbine

Mač Sudbine The Malady and Other Stories: An Andrzej Sapkowski Sampler

The Malady and Other Stories: An Andrzej Sapkowski Sampler The Saga of the Witcher

The Saga of the Witcher The Tower of Fools

The Tower of Fools Vreme Prezira

Vreme Prezira Introducing the Witcher

Introducing the Witcher Stephen Hulin

Stephen Hulin The Time of Contempt

The Time of Contempt The Sword of Destiny

The Sword of Destiny Season of Storms

Season of Storms The Tower of Swallows

The Tower of Swallows The Last Wish: Introducing The Witcher

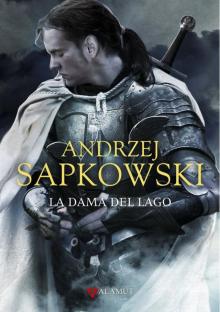

The Last Wish: Introducing The Witcher The Lady of the Lake

The Lady of the Lake