- Home

- Andrzej Sapkowski

The Last Wish Page 14

The Last Wish Read online

Page 14

“BRAAAK! Ghaaa-braaak!” roared Coodcoodak suddenly, to loud applause. Geralt didn't know which animal he was imitating, but he didn't want to meet anything like it. He turned his head and caught the queen's venomously green glance. Drogodar, his lowered head and face concealed by Ms curtain of gray hair, quietly strummed his lute.

“Ah, Geralt,” said Calanthe, with a gesture forbidding a servant from refilling her goblet. “I speak and you remain silent. We're at a feast. We all want to enjoy ourselves. Amuse me. I’m starting to miss your pertinent remarks and perceptive comments. I’d also be pleased to hear a compliment or two, homage or assurance of your obedience. In whichever order you choose.”

“Oh well, your Majesty,” said the witcher, “I’m not a very interesting dinner companion. I’m amazed to be singled out for the honor of occupying this place. Indeed, someone far more appropriate should have been seated here. Anyone you wished. It would have sufficed for you to give them the order, or to buy them. It's only a question of price.”

“Go on, go on.” Calanthe tilted her head back and closed her eyes, the semblance of a pleasant smile on her lips.

“So I’m honored and proud to be sitting by Queen Calanthe of Cintra, whose beauty is surpassed only by her wisdom. I also regard it as a great honor that the queen has heard of me and that, on the basis of what she has heard, does not wish to use me for trivial matters. Last winter Prince Hrobarik, not being so gracious, tried to hire me to find a beauty who, sick of his vulgar advances, had fled the ball, losing a slipper. It was difficult to convince him that he needed a huntsman, and not a witcher.”

The queen was listening with an enigmatic smile.

“Other rulers, too, unequal to you in wisdom, didn't refrain from proposing trivial tasks. It was usually a question of the murder of a stepson, stepfather, stepmother, uncle, aunt—it's hard to mention them all. They were all of the opinion that it was simply a question of price.”

The queen's smile could have meant anything.

“And so I repeat”—Geralt bowed his head a little—“that I can't contain my pride to be sitting next to you, ma'am. And pride means a very great deal to us witchers. You wouldn't believe how much. A lord once offended a witcher's pride by proposing a job that wasn't in keeping with either honor or the witcher's code. What's more, he didn't accept a polite refusal and wished to prevent the witcher from leaving his castle. Afterward, everyone agreed this wasn't one of his best ideas.”

“Geralt,” said Calanthe, after a moment's silence, “you were wrong. You're a very interesting dinner companion.”

Coodcoodak, shaking beer froth from his whiskers and the front of his jacket, craned his neck and gave the penetrating howl of a she-wolf in heat. The dogs in the courtyard, and the entire neighborhood, echoed the howl.

One of the brothers from Strept dipped his finger in his beer and touched up the thick line around the formation drawn by Crach an Craite.

“Error and incompetence!” he shouted. “They shouldn't have done that! Here, toward the wing, that's where they should have directed the cavalry, struck the flanks!”

“Ha!” roared Crach an Craite, whacking the table with a bone and splattering his neighbors’ faces and tunics with sauce. “And so weaken the center? A key position? Ludicrous!”

“Only someone who's blind or sick in the head would miss the opportunity to maneuver in a situation like that!”

“That's it! Quite right!” shouted Windhalm of Attre.

“Who's asking you, you little snot?”

“Snot yourself!”

“Shut your gob or I’ll wallop you—”

“Sit on your arse and keep quiet, Crach,” called Eist Tuirseach, interrupting his conversation with Vissegerd. “Enough of these arguments. Drogodar, sir! Don't waste your talent! Indeed, your beautiful though quiet tunes should be listened to with greater concentration and gravity. Draig Bon-Dhu, stop scoffing and guzzling! You're not going to impress anyone here like that. Pump up your bagpipes and delight our ears with decent martial music. With your permission, noble Calanthe!”

“Oh mother of mine,” whispered the queen to Geralt, raising her eyes to the vault for a moment in silent resignation. But she nodded her permission, smiling openly and kindly.

“Draig Bon-Dhu,” said Eist, “play us the song of the battle of Hochebuz. It won't leave us in any doubt as to the tactical maneuvers of commanders—or as to who acquired immortal fame there! To the health of the heroic Calanthe of Cintra!”

“The health! And glory!” the guests roared, emptying their goblets and clay cups.

Draig Bon-Dhu's bagpipes gave out an ominous drone and burst into a terrible, drawn-out, modulated wail. The guests took up the song, beating out a rhythm on the table with whatever came to hand. Coodcoodak was staring avidly at the goat-leather sack, captivated by the idea of adopting its dreadful tones in his own repertoire.

“Hochebuz,” said Calante, looking at Geralt, “my first battle. Although I fear rousing the indignation and contempt of such a proud witcher, I confess that we were fighting for money. Our enemy was burning villages which paid us levies and we, greedy for our tributes, challenged them on the field. A trivial reason, a trivial battle, a trivial three thousand corpses pecked to pieces by the crows. And look—instead of being ashamed I’m proud as a peacock that songs are sung about me. Even when sung to such awful music.”

Again she summoned her parody of a smile full of happiness and kindness, and answered the toast raised to her by lifting her own, empty, goblet. Geralt remained silent.

“Let's go on.” Calanthe accepted a pheasant leg offered to her by Drogodar and picked at it gracefully. “As I said, you've aroused my interest. I’ve been told that witchers are an interesting caste, but I didn't really believe it. Now I do. When hit, you give a note which shows you're fashioned of pure steel, unlike these men molded from bird shit. Which doesn't, in any way, change the fact that you're here to execute a task. And you'll do it without being so clever.”

Geralt didn't smile disrespectfully or nastily, although he very much wanted to. He held his silence.

“I thought,” murmured the queen, appearing to give her full attention to the pheasant's thigh, “that you'd say something. Or smile. No? All the better. Can I consider our negotiations concluded?”

“Unclear tasks,” said the witcher dryly, “can't be clearly executed.”

“What's unclear? You did, after all, guess correctly. I have plans regarding a marriage alliance with Skellige. These plans are threatened, and I need you to eliminate the threat. But here your shrewdness ends. The supposition that I mistake your trade for that of a hired thug has piqued me greatly. Accept, Geralt, that I belong to that select group of rulers who know exactly what witchers do, and how they ought to be employed. On the other hand, if someone kills as efficiently as you do, even though not for money, he shouldn't be surprised if people credit him with being a professional in that field. Your fame runs ahead of you, Geralt; it's louder than Draig Bon-Dhu's accursed bagpipes, and there are equally few pleasant notes in it.”

The bagpipe player, although he couldn't hear the queen's words, finished his concert. The guests rewarded him with an uproarious ovation and dedicated themselves with renewed zeal to the remains of the banquet, recalling battles and making rude jokes about womenfolk. Coodcoodak was making a series of loud noises, but there was no way to tell if these were yet another animal imitation, or an attempt to relieve his overloaded stomach.

Eist Tuirseach leaned far across the table. “Your Majesty,” he said, “there are good reasons, I am sure, for your dedication to the lord from Fourhorn, but it's high time we saw Princess Pavetta. What are we waiting for? Surely not for Crach an Craite to get drunk? And even that moment is almost here.”

“You're right as usual, Eist.” Calanthe smiled warmly. Geralt was amazed by her arsenal of smiles. “Indeed, I do have important matters to discuss with the Honorable Ravix. I’ll dedicate some time to you too, but you know my

principle: duty then pleasure. Haxo!”

She raised her hand and beckoned the castellan. Haxo rose without a word, bowed, and quickly ran upstairs, disappearing into the dark gallery. The queen turned to the witcher.

“You heard? We've been debating for too long. If Pavetta has stopped preening in front of the looking glass, she'll be here presently. So prick up your ears because I won't repeat this. I want to achieve the ends which, to a certain degree, you have guessed. There can be no other solution. As for you, you have a choice. You can be forced to act by my command—I don't wish to dwell on the consequences of disobedience, although obedience will be generously rewarded—or you can render me a paid service. Note that I didn't say “I can buy you,’ because I’ve decided not to offend your witcher's pride. There's a huge difference, isn't there?”

“The magnitude of this difference has somehow escaped my notice.”

‘Then pay greater attention. The difference, my dear witcher, is that one who is bought is paid according to the buyer's whim, whereas one who renders a service sets his own price. Is that clear?”

“To a certain extent. Let's say, then, that I choose to serve. Surely I should know what that entails?”

“No. Only a command has to be specific and explicit. A paid service is different. I’m interested in the results, nothing more. How you achieve it is your business.”

Geralt, raising his head, met Mousesack's penetrating black gaze. The druid of Skellige, without taking his eyes from the witcher, was crumbling bread in his hands and dropping it as if lost in thought. Geralt looked down. There on the oak table, crumbs, grains of buckwheat and fragments of lobster shell were moving like ants. They were forming runes which joined up—for a moment—into a word. A question.

Mousesack waited without taking his eyes off him. Geralt, almost imperceptibly, nodded. The druid lowered his eyelids and, with a stony face, swiped the crumbs off the table.

“Honorable gentlemen!” called the herald. “Pavetta of Cintra!”

The guests grew silent, turning to the stairs.

Preceded by the castellan and a fair-haired page in a scarlet doublet, the princess descended slowly, her head lowered. The color of her hair was identical to her mother's—ash-gray—but she wore it braided into two thick plaits which reached below her waist. Pavetta was adorned only with a tiara ornamented with a delicately worked jewel and a belt of tiny golden links which girded her long silvery-blue dress at the hips.

Escorted by the page, herald, castellan and Vissegerd, the princess occupied the empty chair between Drogodar and Eist Tuirseach. The knightly islander immediately filled her goblet and entertained her with conversation. Geralt didn't notice her answer with more than a word. Her eyes were permanently lowered, hidden behind her long lashes even during the noisy toasts raised to her around the table. There was no doubt her beauty had impressed the guests—Crach an Craite stopped shouting and stared at Pavetta in silence, even forgetting his tankard of beer. Windhalm of Attre was also devouring the princess with his eyes, flushing shades of red as though only a few grains in the hourglass separated them from their wedding night. Coodcoodak and the brothers from Strept were studying the girl's petite face, too, with suspicious concentration.

“Aha,” said Calanthe quietly, clearly pleased. “And what do you say, Geralt? The girl has taken after her mother. It's even a shame to waste her on that red-haired lout, Crach. The only hope is that the pup might grow into someone with Eist Tuirseach's class. It's the same blood, after all. Are you listening, Geralt? Cintra has to form an alliance with Skellige because the interest of the state demands it. My daughter has to marry the right person. Those are the results you must ensure me.”

“I have to ensure that? Isn't your will alone sufficient for it to happen?”

“Events might take such a turn that it won't be sufficient.”

“What can be stronger than your will?”

“Destiny.”

“Aha. So I, a poor witcher, am to face down a destiny which is stronger than the royal will. A witcher fighting destiny! What irony!”

“Yes, Geralt? What irony?”

“Never mind. Your Majesty, it seems the service you demand borders on the impossible.”

“If it bordered on the possible,” Calanthe drawled, “I would manage it myself. I wouldn't need the famous Geralt of Rivia. Stop being so clever. Everything can be dealt with—it's only a question of price. Bloody hell, there must be a figure on your witchers’ pricelist for work that borders on the impossible. I can guess one, and it isn't low. You ensure me my outcome and I will give you what you ask.”

“What did you say?”

“I’ll give you whatever you ask for. And I don't like being told to repeat myself. I wonder, witcher, do you always try to dissuade your employers as strongly as you are me? Time is slipping away. Answer, yes or no?”

“Yes.”

“That's better. That's better, Geralt. Your answers are much closer to the ideal. They're becoming more like those I expect when I ask a question. So. Discreetly stretch your left hand out and feel behind my throne.”

Geralt slipped his hand under the yellow-blue drapery. Almost immediately he felt a sword secured to the leather-upholstered backrest. A sword well-known to him.

“Your Majesty,” he said quietly, “not to repeat what I said earlier about killing people, you do realize that a sword alone will not defeat destiny?”

“I do.” Calanthe turned her head away. “A witcher is also necessary. As you see, I took care of that.”

“Your Maje—”

“Not another word, Geralt. We've been conspiring for too long. They're looking at us, and Eist is getting angry. Talk to the castellan. Have something to eat. Drink, but not too much. I want you to have a steady hand.”

He obeyed. The queen joined a conversation between Eist, Vissegerd and Mousesack, with Pavetta's silent and dreamy participation. Drogodar had put away his lute and was making up for his lost eating time. Haxo wasn't talkative. The voivode with the hard-to-remember name, who must have heard something about the affairs and problems of Fourhorn, politely asked whether the mares were foaling well. Geralt answered yes, much better than the stallions. He wasn't sure if the joke had been well taken, but the voivode didn't ask any more questions.

Mousesack's eyes constantly sought the witcher's, but the crumbs on the table didn't move again.

Crach an Craite was becoming more and more friendly with the two brothers from Strept. The third, the youngest brother, was paralytic, having tried to match the drinking speed imposed by Draig Bon-Dhu. The skald had emerged from it unscathed.

The younger and less important lords gathered at the end of the table, tipsy, started singing a well-known song—out of tune—about a little goat with horns and a vengeful old woman with no sense of humor.

A curly-haired servant and a captain of the guards wearing the gold and blue of Cintra ran up to Vissegerd. The marshal, frowning, listened to their report, rose, and leaned down from behind the throne to murmur something to the queen. Calanthe glanced at Geralt and answered with a single word. Vissegerd leaned over even further and whispered something more; the queen looked at him sharply and, without a word, slapped her armrest with an open palm. The marshal bowed and passed the command to the captain of the guards. Geralt didn't hear it but he did notice that Mousesack wriggled uneasily and glanced at Pavetta—the princess was sitting motionless, her head lowered.

Heavy footsteps, each accompanied by the clang of metal striking the floor, could be heard over the hum at the table. Everyone raised their heads and turned.

The approaching figure was clad in armor of iron sheets and leather treated with wax. His convex, angular, black and blue breastplate overlapped a segmented apron and short thigh pads. The armor-plated brassards bristled with sharp, steel spikes and the visor, with its densely grated screen extending out in the shape of a dog's muzzle, was covered with spikes like a conker casing.

Clattering and grinding,

the strange guest approached the table and stood motionless in front of the throne.

“Noble queen, honorable gentlemen,” said the newcomer, bowing stiffly. “Please forgive me for disrupting your ceremonious feast. I am Urcheon of Erlenwald.”

“Greetings, Urcheon of Erlenwald,” said Calanthe slowly. “Please take your place at the table. In Cintra we welcome every guest.”

“Thank you, your Majesty.” Urcheon of Erlenwald bowed once again and touched his chest with a fist clad in an iron gauntlet. “But I haven't come to Cintra as a guest but on a matter of great importance and urgency. If your Majesty permits, I will present my case immediately, without wasting your time.”

“Urcheon of Erlenwald,” said the queen sharply, “a praiseworthy concern about our time does not justify lack of respect. And such is your speaking to us from behind an iron trellis. Remove your helmet, and we'll endure the time wasted while you do.”

“My face, your Majesty, must remain hidden for the time being. “With your permission.”

An angry ripple, punctuated here and there with the odd curse, ran through the gathered crowd. Mousesack, lowering his head, moved his lips silently. The witcher felt the spell electrify the air for a second, felt it stir his medallion. Calanthe was looking at Urcheon, narrowing her eyes and drumming her fingers on her armrest.

“Granted,” she said finally. “I choose to believe your motive is sufficiently important. So—what brings you here, Urcheon-without-a-face?”

“Thank you,” said the newcomer. “But I’m unable to suffer the accusation of lacking respect, so I explain that it is a matter of a knight's vows. I am not allowed to reveal my face before midnight strikes.”

Calanthe, raising her hand perfunctorily, accepted his explanation. Urcheon advanced, his spiked armor clanging.

something ends something begins sapkowski

something ends something begins sapkowski The Last Wish

The Last Wish Baptism of Fire

Baptism of Fire Blood of Elves

Blood of Elves Lastavičja Kula

Lastavičja Kula Gospodarica Jezera

Gospodarica Jezera Vatreno Krštenje

Vatreno Krštenje Sezona Oluja

Sezona Oluja Lady of the Lake

Lady of the Lake The Road With No Return

The Road With No Return Time of Contempt

Time of Contempt Mač Sudbine

Mač Sudbine The Malady and Other Stories: An Andrzej Sapkowski Sampler

The Malady and Other Stories: An Andrzej Sapkowski Sampler The Saga of the Witcher

The Saga of the Witcher The Tower of Fools

The Tower of Fools Vreme Prezira

Vreme Prezira Introducing the Witcher

Introducing the Witcher Stephen Hulin

Stephen Hulin The Time of Contempt

The Time of Contempt The Sword of Destiny

The Sword of Destiny Season of Storms

Season of Storms The Tower of Swallows

The Tower of Swallows The Last Wish: Introducing The Witcher

The Last Wish: Introducing The Witcher The Lady of the Lake

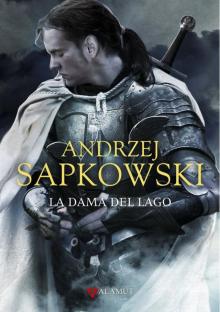

The Lady of the Lake