- Home

- Andrzej Sapkowski

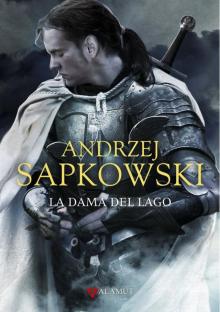

The Saga of the Witcher Page 11

The Saga of the Witcher Read online

Page 11

‘I do, Uncle Vesemir. Geralt explained it to me. I know all that. An ecological niche is—’

‘All right, that’s fine. I know what it is. If Geralt has explained it to you, you don’t have to recite it to me. Let us return to the graveir. Graveirs appear quite rarely, fortunately, because they’re bloody dangerous sons-of-bitches. The smallest wound inflicted by a graveir will infect you with corpse venom. Which elixir is used to treat corpse venom poisoning, Ciri?’

‘“Golden Oriole”.’

‘Correct. But it is better to avoid infection to begin with. That is why, when fighting a graveir, you must never get close to the bastard. You always fight from a distance and strike from a leap.’

‘Hmm . . . And where’s it best to strike one?’

‘We’re just getting to that. Look . . .’

‘Once more, Ciri. We’ll go through it slowly so that you can master each move. Now, I’m attacking you with tierce, taking the position as if to thrust . . . Why are you retreating?’

‘Because I know it’s a feint! You can move into a wide sinistra or strike with upper quarte. And I’ll retreat and parry with a counterfeint!’

‘Is that so? And if I do this?’

‘Auuu! It was supposed to be slow! What did I do wrong, Coën?’

‘Nothing. I’m just taller and stronger than you are.’

‘That’s not fair!’

‘There’s no such thing as a fair fight. You have to make use of every advantage and every opportunity that you get. By retreating you gave me the opportunity to put more force into the strike. Instead of retreating you should have executed a half-pirouette to the left and tried to cut at me from below, with quarte dextra, under the chin, in the cheek or throat.’

‘As if you’d let me! You’ll do a reverse pirouette and get my neck from the left before I can parry! How am I meant to know what you’re doing?’

‘You have to know. And you do know.’

‘Oh, sure!’

‘Ciri, what we’re doing is fighting. I’m your opponent. I want to and have to defeat you because my life is at stake. I’m taller and stronger than you so I’m going to watch for opportunities to strike in order to avoid or break your parry – as you’ve just seen. What do I need a pirouette for? I’m already in sinistra, see? What could be simpler than to strike with a seconde, under the arm, on the inside? If I slash your artery, you’ll be dead in a couple of minutes. Defend yourself!’

‘Haaaa!’

‘Very good. A beautiful, quick parry. See how exercising your wrist has come in useful? And now pay attention – a lot of fencers make the mistake of executing a standing parry and freeze for a second, and that’s just when you can catch them out, strike – like so!’

‘Haa!’

‘Beautiful! Now jump away, jump away immediately, pirouette! I could have a dagger in my left hand! Good! Very good! And now, Ciri? What am I going to do now?’

‘How am I to know?’

‘Watch my feet! How is my body weight distributed? What can I do from this position?’

‘Anything!’

‘So spin, spin, force me to open up! Defend yourself! Good! And again! Good! And again!’

‘Owwww!’

‘Not so good.’

‘Uff . . . What did I do wrong?’

‘Nothing. I’m just faster. Take your guards off. We’ll sit for a moment, take a break. You must be tired, you’ve been running the Trail all morning.’

‘I’m not tired. I’m hungry.’

‘Bloody hell, so am I. And today’s Lambert’s turn and he can’t cook anything other than noodles . . . If he could only cook those properly . . .’

‘Coën?’

‘Aha?’

‘I’m still not fast enough—’

‘You’re very fast.’

‘Will I ever be as fast as you?’

‘I doubt it.’

‘Hmm . . . And are you—? Who’s the best fencer in the world?’

‘I’ve no idea.’

‘You’ve never known one?’

‘I’ve known many who believed themselves to be the best.’

‘Oh! What were they? What were their names? What could they do?’

‘Hold on, hold on, girl. I haven’t got an answer to those questions. Is it all that important?’

‘Of course it’s important! I’d like to know who these fencers are. And where they are.’

‘Where they are? I know that.’

‘Ah! So where?’

‘In cemeteries.’ *

*

‘Pay attention, Ciri. We’re going to attach a third pendulum now – you can manage two already. You use the same steps as for two only there’s one more dodge. Ready?’

‘Yes.’

‘Focus yourself. Relax. Breathe in, breathe out. Attack!’

‘Ouch! Owwww . . . Damn it!’

‘Don’t swear. Did it hit you hard?’

‘No, it only brushed me . . . What did I do wrong?’

‘You ran in at too even a pace, you sped the second half-pirouette up a bit too much, and your feint was too wide. And as a result you were carried straight under the pendulum.’

‘But Geralt, there’s no room for a dodge and turn there! They’re too close to each other!’

‘There’s plenty of room, I assure you. But the gaps are worked out to force you to make arrhythmic moves. This is a fight, Ciri, not ballet. You can’t move rhythmically in a fight. You have to distract the opponent with your moves, confuse his reactions. Ready for another try?’

‘Ready. Start those damn logs swinging.’

‘Don’t swear. Relax. Attack!’

‘Ha! Ha! Well, how about that? How was that, Geralt? It didn’t even brush me!’

‘And you didn’t even brush the second sack with your sword. So I repeat, this is a fight. Not ballet, not acrobatics—What are you muttering now?’

‘Nothing.’

‘Relax. Adjust the bandage on your wrist. Don’t grip the hilt so tightly, it distracts you and upsets your equilibrium. Breathe calmly. Ready?’

‘Yes.’

‘Go!’

‘Ouch! May you—Geralt, it’s impossible! There’s not enough room for a feint and a change of foot. And when I strike from both legs, without a feint . . .’

‘I saw what happens when you strike without a feint. Does it hurt?’

‘No. Not much . . .’

‘Sit down next to me. Take a break.’

‘I’m not tired. Geralt, I’m not going to be able to jump over that third pendulum even if I rest for ten years. I can’t be any faster—’

‘And you don’t have to be. You’re fast enough.’

‘Tell me how to do it then. Half-pirouette, dodge and hit at the same time?’

‘It’s very simple; you just weren’t paying attention. I told you before you started – an additional dodge is necessary. Displacement. An additional half-pirouette is superfluous. The second time round, you did everything well and passed all the pendulums.’

‘But I didn’t hit the sack because . . . Geralt, without a half-pirouette I can’t strike because I lose speed, I don’t have the . . . the, what do you call it . . .’

‘Impetus. That’s true. So gain some impetus and energy. But not through a pirouette and change of foot because there’s not enough time for it. Hit the pendulum with your sword.’

‘The pendulum? I’ve got to hit the sacks!’

‘This is a fight, Ciri. The sacks represent your opponent’s sensitive areas, you’ve got to hit them. The pendulums – which simulate your opponent’s weapon – you have to avoid, dodge past. When the pendulum hits you, you’re wounded. In a real fight, you might not get up again. The pendulum mustn’t touch you. But you can hit the pendulum . . . Why are you screwing your nose up?’

‘I’m . . . not going to be able to parry the pendulum with my sword. I’m too weak . . . I’ll always be too weak! Because I’m a girl!’

‘Come here, gir

l. Wipe your nose, and listen carefully. No strongman, mountain-toppling giant or muscle-man is going to be able to parry a blow aimed at him by a dracolizard’s tail, gigascorpion’s pincers or a griffin’s claws. And that’s precisely the sort of weapons the pendulum simulates. So don’t even try to parry. You’re not deflecting the pendulum, you’re deflecting yourself from it. You’re intercepting its energy, which you need in order to deal a blow. A light, but very swift deflection and instantaneous, equally swift blow from a reverse half-turn is enough. You’re picking impetus up by rebounding. Do you see?’

‘Mhm.’

‘Speed, Ciri, not strength. Strength is necessary for a lumberjack axing trees in a forest. That’s why, admittedly, girls are rarely lumberjacks. Have you got that?’

‘Mhm. Start the pendulums swinging.’

‘Take a rest first.’

‘I’m not tired.’

‘You know how to now? The same steps, feint—’

‘I know.’

‘Attack!’

‘Haaa! Ha! Haaaaa! Got you! I got you, you griffin! Geraaaalt! Did you see that?’

‘Don’t yell. Control your breathing.’

‘I did it! I really did it!! I managed it! Praise me, Geralt!’

‘Well done, Ciri. Well done, girl.’

In the middle of February, the snow disappeared, whisked away by a warm wind blowing from the south, from the pass.

Whatever was happening in the world, the witchers did not want to know.

In the evenings, consistently and determinedly, Triss guided the long conversations held in the dark hall, lit only by the bursts of flames in the great hearth, towards politics. The witchers’ reactions were always the same. Geralt, a hand on his forehead, did not say a word. Vesemir nodded, from time to time throwing in comments which amounted to little more than that ‘in his day’ everything had been better, more logical, more honest and healthier. Eskel pretended to be polite, and neither smiled nor made eye contact, and even managed, very occasionally, to be interested in some issue or question of little importance. Coën yawned openly and looked at the ceiling, and Lambert did nothing to hide his disdain.

They did not want to know anything, they cared nothing for dilemmas which drove sleep from kings, wizards, rulers and leaders, or for the problems which made councils, circles and gatherings tremble and buzz. For them, nothing existed beyond the passes drowning in snow or beyond the Gwenllech river carrying ice-floats in its leaden current. For them, only Kaer Morhen existed, lost and lonely amongst the savage mountains.

That evening Triss was irritable and restless – perhaps it was the wind howling along the great castle’s walls. And that evening they were all oddly excited – the witchers, apart from Geralt, were unusually talkative. Quite obviously, they only spoke of one thing – spring. About their approaching departure for the Trail. About what the Trail would have in store for them – about vampires, wyverns, leshys, lycanthropes and basilisks.

This time it was Triss who began to yawn and stare at the ceiling. This time she was the one who remained silent – until Eskel turned to her with a question. A question which she had anticipated.

‘And what is it really like in the south, on the Yaruga? Is it worth going there? We wouldn’t like to find ourselves in the middle of any trouble.’

‘What do you mean by trouble?’

‘Well, you know . . .’ he stammered, ‘you keep telling us about the possibility of a new war . . . About constant fighting on the borders, about rebellions in the lands invaded by Nilfgaard. You said they’re saying the Nilfgaardians might cross the Yaruga again—’

‘So what?’ said Lambert. ‘They’ve been hitting, killing and striking against each other constantly for hundreds of years. It’s nothing to worry about. I’ve already decided – I’m going to the far South, to Sodden, Mahakam and Angren. It’s well known that monsters abound wherever armies have passed. The most money is always made in places like that.’

‘True,’ Coën acknowledged. ‘The neighbourhood grows deserted, only women who can’t fend for themselves remain in the villages . . . scores of children with no home or care, roaming around . . . Easy prey attracts monsters.’

‘And the lord barons and village elders,’ added Eskel, ‘have their heads full of the war and don’t have the time to defend their subjects. They have to hire us. It’s true. But from what Triss has been telling us all these evenings, it seems the conflict with Nilfgaard is more serious than that, not just some local little war. Is that right, Triss?’

‘Even if it were the case,’ said the magician spitefully, ‘surely that suits you? A serious, bloody war will lead to more deserted villages, more widowed women, simply hordes of orphaned children—’

‘I can’t understand your sarcasm.’ Geralt took his hand away from his forehead. ‘I really can’t, Triss.’

‘Nor I, my child.’ Vesemir raised his head. ‘What do you mean? Are you thinking about the widows and children? Lambert and Coën speak frivolously, as youngsters do, but it is not the words that are important. After all, they—’

‘. . . they defend these children,’ she interrupted crossly. ‘Yes, I know. From the werewolf who might kill two or three a year, while a Nilfgaardian foray can kill and burn an entire settlement in an hour. Yes, you defend orphans. While I fight that there should be as few of those orphans as possible. I’m fighting the cause, not the effect. That’s why I’m on Foltest of Temeria’s council and sit with Fercart and Keira Metz. We deliberate on how to stop war from breaking out and, should it come to it, how to defend ourselves. Because war is constantly hovering over us like a vulture. For you it’s an adventure. For me, it’s a game in which the stakes are survival. I’m involved in this game, and that’s why your indifference and frivolity hurt and insult me.’

Geralt sat up and looked at her.

‘We’re witchers, Triss. Can’t you understand that?’

‘What’s there to understand?’ The enchantress tossed her chestnut mane back. ‘Everything’s crystal-clear. You’ve chosen a certain attitude to the world around you. The fact that this world might at any moment fall to pieces has a place in this choice. In mine, it doesn’t. That’s where we differ.’

‘I’m not sure it’s only there we differ.’

‘The world is falling to ruins,’ she repeated. ‘We can watch it happen and do nothing. Or we can counteract it.’

‘How?’ He smiled derisively. ‘With our emotions?’

She did not answer, turning her face to the fire roaring in the hearth.

‘The world is falling to ruins,’ repeated Coën, nodding his head in feigned thoughtfulness. ‘How many times I’ve heard that.’

‘Me, too,’ Lambert grimaced. ‘And it’s not surprising – it’s a popular saying of late. It’s what kings say when it turns out that a modicum of brains is necessary to rule after all. It’s what merchants say when greed and stupidity have led them to bankruptcy. It’s what wizards say when they start to lose their influence on politics or income. And the person they’re speaking to should expect some sort of proposal straight away. So cut the introduction short, Triss, and present us with your proposition.’

‘Verbal squabbling has never amused me,’ the enchantress declared, gauging him with cold eyes, ‘or displays of eloquence which mock whoever you’re talking to. I don’t intend to take part in anything like that. You know only too well what I mean. You want to hide your heads in the sand, that’s your business. But coming from you, Geralt, it’s a great surprise.’

‘Triss.’ The white-haired witcher looked her straight in the eyes again. ‘What do you expect from me? To take an active part in the fight to save a world which is falling to pieces? Am I to enlist in the army and stop Nilfgaard? Should I, if it comes to another battle for Sodden, stand with you on the Hill, shoulder to shoulder, and fight for freedom?’

‘I’d be proud,’ she said quietly, lowering her head. ‘I’d be proud and happy to fight at your side.’

&nb

sp; ‘I believe that. But I’m not gallant enough. Nor valiant enough. I’m not suited to be a soldier or a hero. And having an acute fear of pain, mutilation and death is not the only reason. You can’t stop a soldier from being frightened but you can give him motivation to help him overcome that fear. I have no such motivation. I can’t have. I’m a witcher: an artificially created mutant. I kill monsters for money. I defend children when their parents pay me to. If Nilfgaardian parents pay me, I’ll defend Nilfgaardian children. And even if the world lies in ruin – which does not seem likely to me – I’ll carry on killing monsters in the ruins of this world until some monster kills me. That is my fate, my reason, my life and my attitude to the world. And it is not what I chose. It was chosen for me.’

‘You’re embittered,’ she stated, tugging nervously at a strand of hair. ‘Or pretending to be. You forget that I know you, so don’t play the unfeeling mutant, devoid of a heart, of scruples and of his own free will, in front of me. And the reasons for your bitterness, I can guess and understand. Ciri’s prophecy, correct?’

‘No, not correct,’ he answered icily. ‘I see that you don’t know me at all. I’m afraid of death, just like everyone else, but I grew used to the idea of it a very long time ago – I’m not under any illusions. I’m not complaining about fate, Triss – this is plain, cold calculation. Statistics. No witcher has yet died of old age, lying in bed dictating his will. Not a single one. Ciri didn’t surprise or frighten me. I know I’m going to die in some cave which stinks of carcases, torn apart by a griffin, lamia or manticore. But I don’t want to die in a war, because they’re not my wars.’

‘I’m surprised at you,’ she replied sharply. ‘I’m surprised that you’re saying this, surprised by your lack of motivation, as you learnedly chose to describe your supercilious distance and indifference. You were at Sodden, Angren and Transriver. You know what happened to Cintra, know what befell Queen Calanthe and many thousands of people there. You know the hell Ciri went through, know why she cries out at night. And I know, too, because I was also there. I’m afraid of pain and death too, even more so now than I was then – I have good reason. As for motivation, it seems to me that back then I had just as little as you. Why should I, a magician, care about the fates of Sodden, Brugge, Cintra or other kingdoms? The problems of having more or less competent rulers? The interests of merchants and barons? I was a magician. I, too, could have said it wasn’t my war, that I could mix elixirs for the Nilfgaardians on the ruins of the world. But I stood on that Hill next to Vilgefortz, next to Artaud Terranova, next to Fercart, next to Enid Findabair and Filippa Eilhart, next to your Yennefer. Next to those who no longer exist – Coral, Yoël, Vanielle . . . There was a moment when out of sheer terror I forgot all my spells except for one – and thanks to that spell I could have teleported myself from that horrific place back home, to my tiny little tower in Maribor. There was a moment, when I threw up from fear, when Yennefer and Coral held me up by the shoulders and hair—’

something ends something begins sapkowski

something ends something begins sapkowski The Last Wish

The Last Wish Baptism of Fire

Baptism of Fire Blood of Elves

Blood of Elves Lastavičja Kula

Lastavičja Kula Gospodarica Jezera

Gospodarica Jezera Vatreno Krštenje

Vatreno Krštenje Sezona Oluja

Sezona Oluja Lady of the Lake

Lady of the Lake The Road With No Return

The Road With No Return Time of Contempt

Time of Contempt Mač Sudbine

Mač Sudbine The Malady and Other Stories: An Andrzej Sapkowski Sampler

The Malady and Other Stories: An Andrzej Sapkowski Sampler The Saga of the Witcher

The Saga of the Witcher The Tower of Fools

The Tower of Fools Vreme Prezira

Vreme Prezira Introducing the Witcher

Introducing the Witcher Stephen Hulin

Stephen Hulin The Time of Contempt

The Time of Contempt The Sword of Destiny

The Sword of Destiny Season of Storms

Season of Storms The Tower of Swallows

The Tower of Swallows The Last Wish: Introducing The Witcher

The Last Wish: Introducing The Witcher The Lady of the Lake

The Lady of the Lake